The official place names and administrative boundary lines drawn on maps don’t always tell the whole story. In Great Britain there are countless places which are only referred to informally or colloquially by their inhabitants, which don’t always appear on Ordnance Survey maps or which have never been officially defined by the government. The language and terminology used by citizens to describe their local places and spaces is known as vernacular geography.

Vernacular geography is a fascinating subject and could be used by people to describe any topographical feature such as settlements, woodlands, fields, hills, water bodies and tracks. Terms could also be used to describe imprecise, informal geographic regions, such as “The Midlands” or “The West Country”. Some of these places and vague regions with vernacular names have evolved from spaces long lost to history, such as ancient parishes and landmarks, others have sprung up around thoroughfares and modern transport and social hubs.

I recently completed my thesis for a MSc in Geographical Information Technologies through UNIGIS with sponsorship and support from Centremaps at Laser Surveys. My thesis was titled “Exploring vernacular perceptions of spatial entities: A case study using social media data and R for delimiting vague, informal neighbourhoods in Central London, UK”. The premise of the study was to study the informal nature of how citizens discuss and conceive geographic regions, in this case neighbourhoods, by using data from the social media service Twitter.

Vernacular geography has traditionally been difficult to capture and was previously studied using face to face interviews and collecting questionnaires and sketch maps directly from citizens. This was time consuming and, with limited time and resources, could only gather a small sample of people’s opinions. However, the prefoliation of social media services and GPS enabled mobile devices now offers researchers an opportunity to collect enormous amounts of geo-referenced information concerning vernacular geography. People are unconsciously and unknowingly volunteering this information about vernacular geography merely by posting a status update or photo on the internet. This type of data, which could sometimes be described as “Big Data”, due to its sheer volume, contributes to field of study and category of geographic data called Volunteered Geographic Information, or VGI.

In my thesis a dataset from the social media platform Twitter, which consisted of thousands of individual GPS referenced Tweets, was captured and analysed in order demonstrate whether geodata from social media is a feasible method for spatially defining vague, vernacular neighbourhood units in Inner London. Tweets can be collected from Twitter, for research purposes, and downloaded as files which consist of many fields including; the actual Tweet status update text, date and time of Tweet, Twitter username and the latitude and longitude of the geographic location that the Tweet was sent from. The latitude and longitude values can then be used to plot points on a map of Tweet locations and allow for spatial analysis.

A vernacular neighbourhood is a neighbourhood which has no fixed or official government defined boundary, but which is often referred to by citizens colloquially. An example of such a neighbour in London is Soho. These types of colloquial neighbourhood names, and vernacular geography in general, has some important applications. The emergency services find these types of conversational, casual indications of place invaluable when locating reported incidents. There are commercial applications for deliveries and in-vehicle navigation and government uses for the allocation of services and collection of census data. Above all, neighbourhoods form, often overlapping, geographical regions that people and communities can relate to and feel associated with.

The methodology of the research used open source R statistical software to connect to the Twitter API, which gives access to its Tweets so that they can be downloaded. Tweets were harvested by keyword and hashtag searches for London neighbourhood names within the text field of the Tweets. An example of such a Tweet might be: “I’m at Gail’s Artisan Bakery in Soho #Soho”. Tweets were only downloaded which were sent from within the Inner London study area. All statistical analysis, graphics and maps were completed using the spatial capabilities of the R software and utilised some the thousands of user-contributed code libraries. The image below shows all of the tweets collected for each London neighbourhood. Tweets are represented as individual points and coloured depending on the neighbourhood contained within the Tweet text.

As can be seen form the above map, there were distinct groupings of Tweets depending on the neighbourhoods mentioned in the Tweets, this suggests that social media data can be a valuable source for capturing vernacular geography. From these results it was also possible to attempt to mark-out where these vernacular neighbourhoods could be located, in order to give them fixed boundaries.

Twitter data was seen to both mirror the physical form of the underlying topography of London and reflect the social character of the city’s land use. This was seen in the low density of Tweets collected in business areas such as the City of London and also in residential areas. This was in contrast to the high number of Tweets collected in neighbourhoods associated with leisure, recreation, entertainment and shopping such as Covent Garden and Shoreditch. This can clearly be seen in the Tweet density map below, where the lighter colouring and closer contouring indicates a higher density of Tweets.

The study also revealed factors which may have contributed to vernacular neighbourhood demarcation such as physical barriers like rivers, parks and roads and landmarks such as transport hubs and monuments. The map below shows the vernacular neighbourhood of Waterloo in relation to the Train station which forms the basis of the neighbourhood.

The following map also demonstrates how vernacular neighbourhoods form around their namesake topographical feature. It shows the Strand vernacular neighbourhood with the famous Strand thoroughfare superimposed on top.

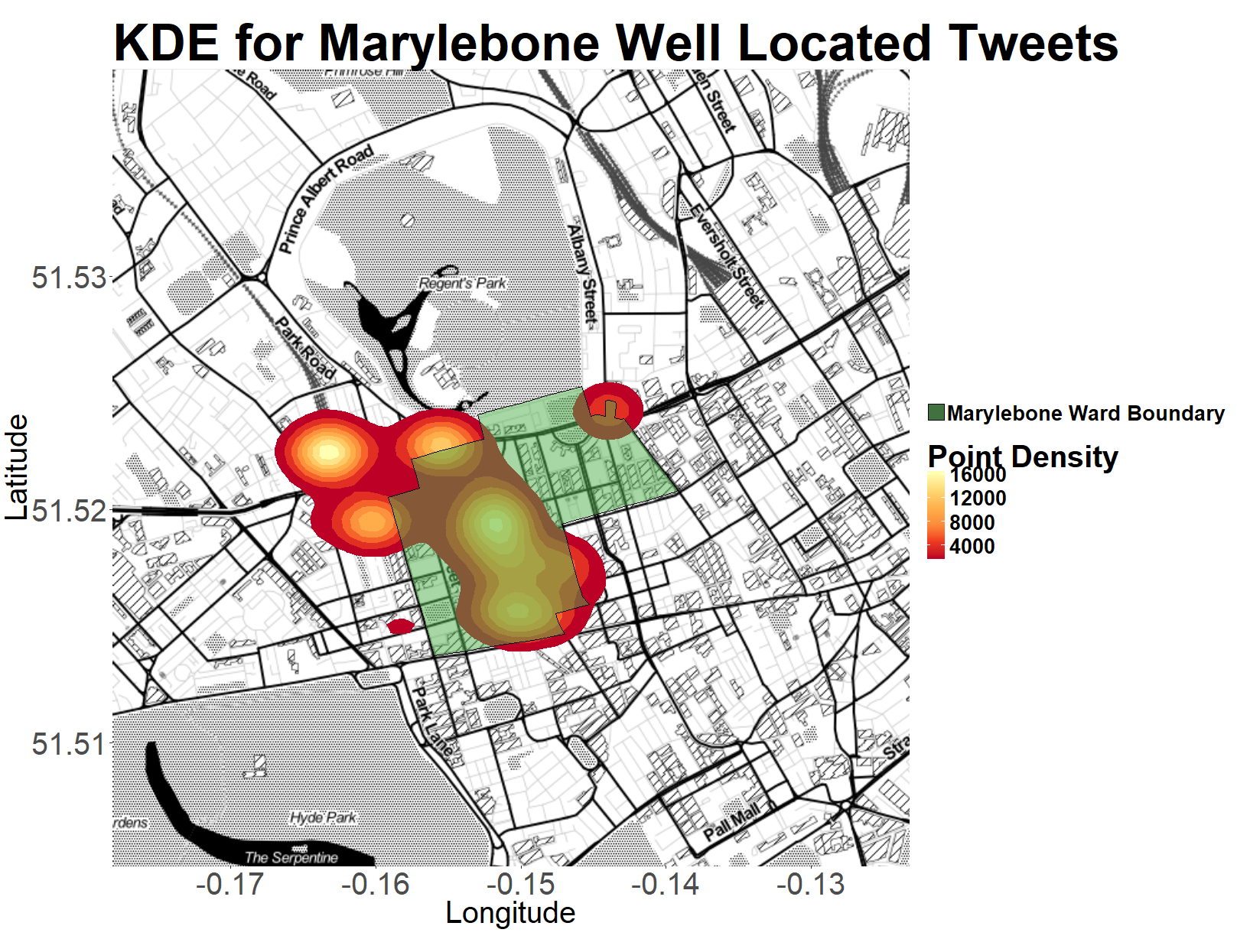

Some comparisons between Tweets collected for particular neighbourhoods and official administrative boundaries were also made. The image below shows the density of Tweets with keywords for Marylebone with the official government boundary for the ward of Marylebone overlaid.

These methods could be applied to any subject and geographic location by altering the keywords and hashtags that are searched the study area can also be easily changed by altering the geographical parameters of the call to the Twitter API. So, for example if you wanted to what study which football teams people were Tweeting about in different areas of Glasgow, you’d just need to change the search parameters.

(All base map tiles by Stamen Design, under CC BY 3.0. Data by OpenStreetMap, under ODbL.)